A house that can grow, float, and stays cool all year

Discover a climate-smart house that is changing the tide in Bangladesh, one of the world's most climate-vulnerable nations.

BY NAFISA ISLAM

BY NAFISA ISLAM

This story was originally published on The Good Feed. It has been republished here.

It was a suffocating 35 degrees. Humidity had just hit 70%. I had refilled my water bottle three times by 11 am. Days like this are increasingly common in Bangladesh, with month-long heat waves that now reach up to 42 degrees (108F), the highest temperatures recorded in the last 76 years. There’s no respite inside either, with temperatures often observed higher inside houses than outside.

I was in the heat to find a solution to living in it. In Dhaka, Bangladesh’s capital, one of these solutions is an amphibious house.

The amphibious house with its front yard that has an aquaponics setup and a ramp for persons with disabilities to access the entrance. © Shamim Hossain, BRAC 2025

The amphibious house with its front yard that has an aquaponics setup and a ramp for persons with disabilities to access the entrance. © Shamim Hossain, BRAC 2025

The amphibious house is built for the future. Made of earth blocks, which insulate significantly more effectively than concrete bricks, the house is a constant 26°C year round. The blocks allow the house to ‘breathe’ (self-ventilate), inspired by the human body’s own system for regulating temperature. These earth blocks are also stronger, cheaper and greener than conventional bricks.

The amphibious house is disaster-resilient, with the ability to float during floods and remain on ground during dry periods, withstand cyclones, and contains the infrastructure – agriculture, water and power – that meets the basic needs of its residents during climate disasters. The house is also net-zero, with the emissions created through production offset by green features throughout the house.

What does all this cost? Between BDT 5 lakhs (USD $4000) for a one bedroom house to BDT 25 lakhs (USD $20,000) for a four bedroom house.

The amphibious house costs less than half the price per square foot of a conventional house in Bangladesh and 30% less than a common tin-shed house.”

Building for a hotter future

Bangladesh is known for flooding and cyclones, but unprecedented temperatures in the last three years saw heat-related deaths, millions of students unable to attend school, and highways melting.

Neighboring India is already predicted to be one of the first places in the world to experience heat waves that break the human survivability limit. Bangladesh has a similar climate and an even higher population density.

Side view of the amphibious house. © Shamim Hossain, BRAC 2025

Side view of the amphibious house. © Shamim Hossain, BRAC 2025

Cool architecture has a long history in Bangladesh. An example can be seen in the 17th century Tahkhana Complex, or ‘temperature control unit’ (‘cool palace’ in Persian) in rural Chapainawabganj. Electricity did not exist then, so Mughal architects designed buildings that functioned in harmony with natural elements. This included integrating plants and large water bodies, prioritizing large courtyards and gardens, and orienting walls and windows to optimize natural light and wind flows.

As Bangladesh has industrialized, buildings have modernized, and traditional cool building methods have largely disappeared in cities. With temperatures soaring, people are starting to look back to plan for the future.”

The amphibious house is an attempt to go back to Bangladesh’s roots while incorporating the benefits of modern innovation.

A breath of fresh air

Bangladesh’s air is among the most polluted in the world. While the country has made some of the world’s most impressive gains in life expectancy, jumping from 50 to 72 years, air pollution has now reduced the average Bangladeshi’s life by 6.7 years. Approximately 1 out of 5 premature infant deaths in Bangladesh are due to air pollution. The most significant source of this pollution is industrial emissions, particularly from brick kilns.

Low carbon bricks, such as those used in the amphibious house, are made without kilns. Clay soil is compressed with sand and mixed with additives like lime which cause a chemical reaction that leads to carbon dioxide being absorbed.

The reaction makes the bricks so strong that they do not need to be fired in a kiln–making it the perfect solution to the brick kiln ban that combines both traditional and modern technology.”

Left: The earth block used to build the amphibious house. Right: The machine used to create earth blocks. © Shamim Hossain, BRAC 2025

Left: The earth block used to build the amphibious house. Right: The machine used to create earth blocks. © Shamim Hossain, BRAC 2025

An important functionality of the bricks–emissions. The construction industry in Bangladesh makes up more than one-fourth of the country’s total greenhouse gas emissions, and about 23,300 tons of particulate matter, 1.8 million tons of carbon dioxide, 302,000 tons of carbon monoxide and other highly hazardous compounds are released from brick kilns annually in Dhaka alone. There are around 7,000 conventional fire-brick factories in Bangladesh, producing approximately 23 billion bricks annually. These emit around 15 million tons of CO₂, accounting for about 17% of the country’s total emissions.

The Government of Bangladesh has been actively shutting down brick kilns that do not use eco-friendly technology and aim to ban all brick kilns by 2025. Bangladesh’s ‘National Adaptation Plan for Reducing Short-lived Climate Pollutants’ aims to reduce black carbon emissions by 40% and methane emission by 17% in 2030 compared to a business as usual scenario. Low carbon bricks have 10 times less carbon emissions compared to conventional bricks and can help to tackle the challenge at the source.

Preparation for anything

In addition to the benefits for heat, air pollution, and emissions, the amphibious house has a unique benefit: the people living in it are equipped to basically survive anything. This is particularly important in Bangladesh, which has been ranked the seventh most extreme disaster risk-prone country in the world, and where disasters often trap people in their houses – or wherever they are when a crisis hits – for prolonged periods. People caught in the floods in August this year were trapped in their homes for almost four days before they could be rescued.

The vertical posts that keep the amphibious house anchored during a flood to prevent lateral movement when the house floats. © Shamim Hossain, BRAC 2025

The vertical posts that keep the amphibious house anchored during a flood to prevent lateral movement when the house floats. © Shamim Hossain, BRAC 2025

People living in the amphibious house will not have to worry about being trapped or stranded during a flood as they can access basic critical services in their homes. The house stays afloat during floods and, while people are cut off from services, it equips them to produce their own food, water and energy. The buoyant base of the house makes the house float. Four vertical posts are set at the corners to prevent lateral movement during flotation. As floodwater enters the area, it fills a cavity under the foundation, which makes the buoyant base lift the house during floods–like a pontoon.

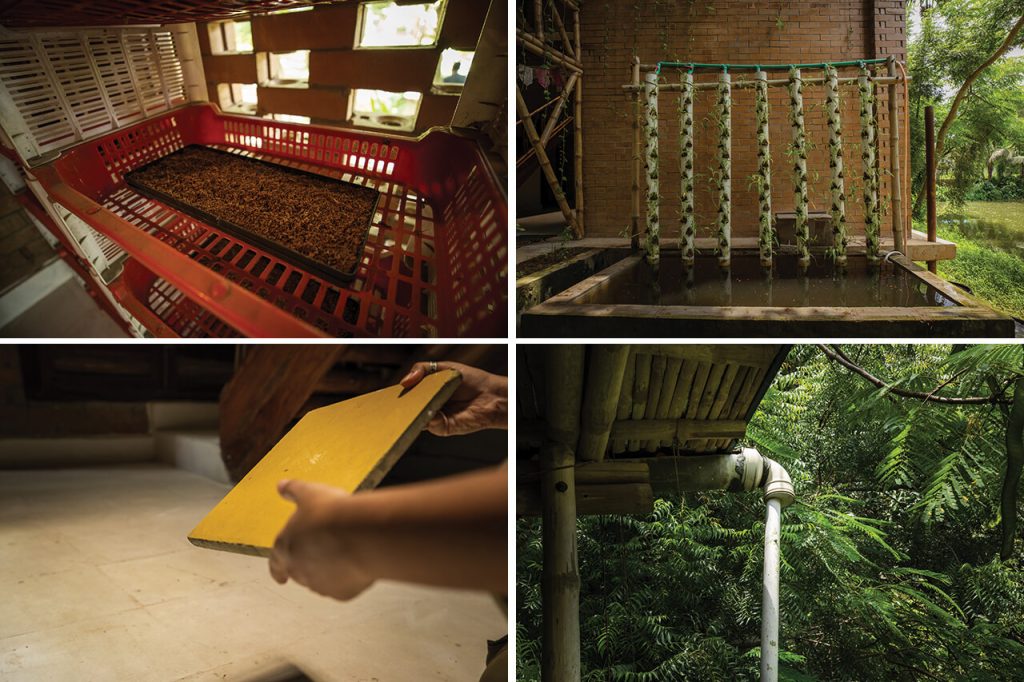

Top-left: Indoor permaculture set-up. Bottom-left: Carbon tile. Bottom-right: A pipe from the rainwater harvesting system. Top-right: Outdoor aquaponics set-up. © Shamim Hossain, BRAC 2025

Top-left: Indoor permaculture set-up. Bottom-left: Carbon tile. Bottom-right: A pipe from the rainwater harvesting system. Top-right: Outdoor aquaponics set-up. © Shamim Hossain, BRAC 2025

Food comes from an indoor permaculture set-up, outdoor aquaponics setup and poultry, and water is collected from the sky and treated before reusing for other purposes in the house. 17,000 liters of water can be stored. Energy comes from the ceiling and walls; the ceiling is made of carbon tiles, and the walls are painted with clay paint. The house uses a 5 kW solar panel system, with options for off-grid battery storage and on-grid use along with low-cost renewable options like a wind turbine and a solar concentrator for added energy generation.

From Bangladesh to the world

The amphibious house was piloted by the University of Dundee and Resilience Solutions in Bangladesh, with strategic collaboration from BRAC University’s Centre for Climate Change and Environmental Research (C3ER), and won the UN’s prestigious Risk Award in 2019 for strength, durability, and sustainability. It continues to be developed in two more phases with funds from Munich Re Foundation and the Scottish Government respectively.

Interior of the floating house showcasing the curling staircase. © Shamim Hossain, BRAC 2025

Interior of the floating house showcasing the curling staircase. © Shamim Hossain, BRAC 2025

As an added bonus, on top of all the functional benefits, the house is beautiful. Sunlight pours in through the large windows and gaps between the bamboo, flooding the clay-painted walls with warm, honeyed light. It has a grand, curling bamboo staircase as the centerpiece and an opening on the roof that creates a spotlight on the ground. Resin protects the outer part of the bamboo from water while natural salts like boric acid and borax is used to treat the bamboo. These salts are non-toxic and alters the sweet carbohydrates stored in the bamboo stem, making it bitter and thereby making it resistant to termites and fungal growth.

Large windows to optimize natural light and wind flows. © Shamim Hossain, BRAC 2025

Large windows to optimize natural light and wind flows. © Shamim Hossain, BRAC 2025

While the amphibious house and the components it is built out of have great features, there are some limitations. The low carbon bricks are heavy and need a factory to scale and supply–something which has not happened yet. In countries like the UK, Denmark and the United States, large-scale production of low carbon bricks is underway. In Bangladesh, large-scale production and widespread adoption are facing challenges. The country is making some changes but policy ambition, financing mechanisms, and market education are not aligned to scale low carbon bricks. Scaling the very building blocks of the amphibious house has been difficult to further scale the house.

It will take time to make people see amphibious houses as a home for the future, particularly in flood-prone areas, instead of a niche intervention.

Interior of the first floor of the amphibious house. © Shamim Hossain, BRAC 2025

Interior of the first floor of the amphibious house. © Shamim Hossain, BRAC 2025

The amphibious house not only makes sense for the global south – countries like Bangladesh – but can be implemented across the world. It is built in a box style, a popular design in many countries, and the jute fiber in the bricks can be replaced with other locally-available fibers.

The construction industry is a key contributor to the climate crisis. Increasingly, however, it is also becoming a key provider of solutions.

As we enter the period of ‘global boiling’, we need to build differently for the future. As I contemplate leaving this beautiful house, and tackling the sweat and smog outside again, it has never felt more urgent.

BRAC University’s Centre for Climate Change and Environmental Research (C3ER) was established in 2011, with the vision of developing sustainable and adaptive solutions for society.

Nasifa Islam is a Communications Specialist at BRAC.