BRAC celebrates 50 years of igniting hope

Today marks the 50th anniversary of BRAC’s founding in Bangladesh in 1972 in the wake of a war that secured the nation’s independence and a devastating cyclone that left it paralyzed.

BY BRAC USA

From those beginnings, “a smoldering ruin,” BRAC has evolved to become the world’s largest Southern-based international development organization. Today, thanks to our committed supporters and partners, we reach over 100 million people in 11 countries with proven poverty innovations.

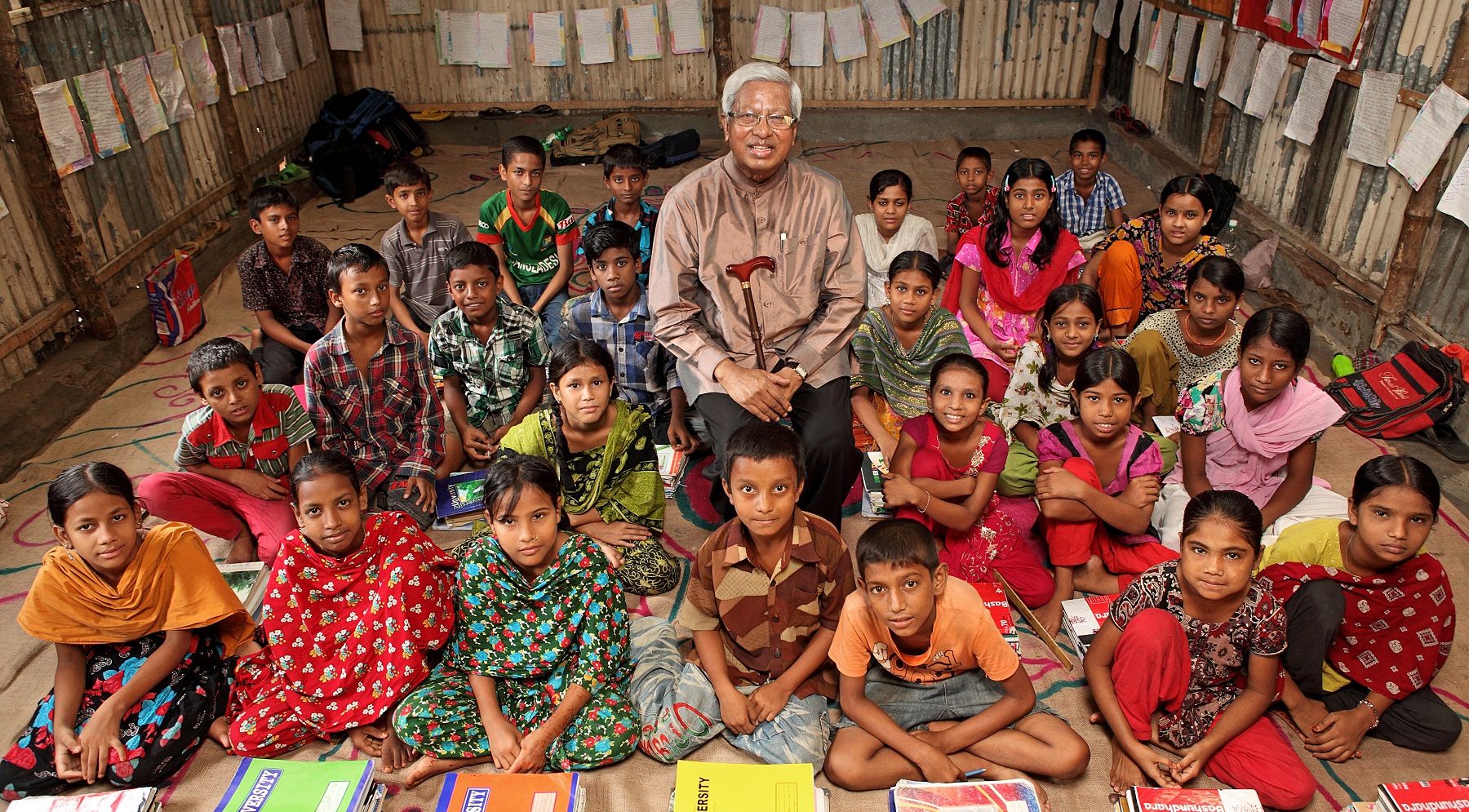

BRAC’s founder, Sir Fazle Hasan Abed, believed unquestioningly in the power of people. He built BRAC on that belief. Poverty and inequality are human-made, so they can be unmade. For 50 years, BRAC has proven that people in situations of poverty and inequality can tackle their own challenges—with the right tools, knowledge and opportunities—and that communities are the most powerful drivers of change.

As we celebrate BRAC’s history, we are thrilled to share an excerpt from a soon-to-be-published biography of our founder that reminds us of how far we’ve come – and of the challenges and opportunities that lie ahead.

We know our work is far from done. Thank you for remaining committed to BRAC’s journey. There is almost no challenge we cannot overcome together. Ignited by hope, we can unmake poverty and inequality.

From a Smoldering Ruin: Tales From the Birth of BRAC

—By Scott MacMillan

(Editor’s note: Scott MacMillan is the author of the forthcoming book Hope Over Fate: Fazle Hasan Abed and the Science of Ending Global Poverty, from which this is adapted. The book will be released in the United States by Rowman & Littlefield on August 1, 2022. Reprinted by permission of the publisher.)

Sarabala was still cooking breakfast when the Pakistan Army arrived to burn her village, Anandapur, to the ground.

It was a gray morning in June 1971, during the Bangladesh Liberation War. Until now, perhaps the saddest moment of Sarabala’s life had been her wedding day, four years earlier. She had cried when her parents told her she was getting married and would soon belong to another family, far away. “I didn’t know who these people were, how they were going to treat me, or where I was going to live,” she recalled. For the monsoon wedding, the bridegroom traveled two hours by boat to reach her parents’ village. Candles and lanterns lit the ceremony, and the night air filled with the sound of flutes and the dhol, a traditional drum that hangs from the player’s neck. Sarabala wept throughout.

Now she lived in Anandapur, her husband’s village, a predominantly Hindu community in an area called Sulla (pronounced “shallah”). The village sat on a hillock rising above the haor, the lowland of northeast Bengal, in what was then East Pakistan. The haor is a geographical oddity, with tracts of land submerged for much of each year. In the hills to the north, in India’s Meghalaya State, it rains as much as fifteen inches a day, more than any other place on earth. The rainwater coming off these hills creates a depression, often described as a giant saucer or bowl. During the monsoon, the saucer fills and overflows, turning much of Sulla into a vast inland sea.

Within a year Sarabala had a daughter, Shujila. The war started in March 1971, when Shujila was three. By the summer, the residents of Anandapur had begun hearing gunfire in the distance. The Pakistan Army had a reputation for brutality, especially against Hindus, but the other villagers assured Sarabala there was nothing to fear. The soldiers had no reason to come to such a remote place, they told her. Yet the gunfire grew closer day by day, until that morning in June when it was upon them.

Panic set in as Sarabala cooked breakfast over an outdoor fire. Her neighbors began to flee. There were about ten flat-bottomed rowboats on the shore of the village. Without stopping to gather possessions, the entire population of Anandapur boarded these boats, pushed off and began rowing. Out on the water, Sarabala clung to her daughter and looked back to see soldiers torching the entire village. All around her, plumes of smoke filled the sky. They joined a flotilla of wooden skiffs from other villages, thousands of people rowing north. They rowed for three days. At a place just across the Indian border called Balat, they settled on a wooded hill. They cut the trees to make shelter, eating leaves and whatever else they could find. In the days and months to come, tens of thousands of others joined them, until not a patch of spare ground remained.

Death was common. Cholera broke out. Locals would occasionally set fire to the camps to try to drive them out, burning the refugees alive. In Sarabala’s section of the camp, one doctor cared for three thousand people. They dug graves in the sand. One day, Shujila, age three, said to her mother, “You’re going to put me in the sand like that.”

***

The Bangladesh Liberation War of 1971 had begun on the night of March 25, 1971, when West Pakistani troops launched a coordinated attack on Bengali regiments and police units in Dhaka. The war soon engulfed the entire country, reaching as far as Sarabala’s village in the remote northeast. In December, fearing the growing involvement of India, which was supporting the Bangladeshi forces, Pakistan launched a preemptive attack on Indian air bases, a miscalculation that cost them the war and gained Bangladesh its freedom. On December 16, combined Indian-Bangladeshi forces entered Dhaka. More than ninety thousand Pakistani soldiers surrendered, one of the largest military surrenders in history. After nine brutal months, the war was over.

Sarabala and Shujila survived. Sarabala cannot remember the exact day she realized Bangladesh had won its freedom. For a week, she witnessed small rallies, groups of people running with the flag used by liberation forces—a yellow shape of Bangladesh in a red disc, surrounded by green field—shouting, “Joy Bangla!” (roughly, “Victory to Bengal”). “I kept hearing it, but I didn’t believe it until I saw the people close to me heading back,” she said. She, her husband and daughter set off on foot and eventually reached the hillock where Anandapur had once stood. Their homes were gone, but the family had survived, three of ten million returning refugees.

Thousands of miles away, in London, another Bangladeshi war refugee, a well-to-do accountant named Fazle Hasan Abed, awaited news from his best friend, Viquar Chowdhury, a lawyer who had just entered the newly liberated country from the north. Abed and Viquar had started a small activist group in London called Help Bangladesh to fundraise, lobby foreign governments and provide relief in the sprawling refugee camps in India, including Balat. During the last weeks of fighting, Viquar had been visiting camps on the northern border. He had followed returning refugees, Sarabala among them, to their villages in Sulla.

Viquar wrote a letter to Abed from Sylhet, the nearest city. The letter, which reached London four days later, offered a grim report. Many refugees had returned to find nothing left of their homes, he wrote. “He asked me to come home as quickly as possible and to bring as much money as I could,” Abed recalled.

The only thing of value that Abed owned at this point was half a house in the district of Camden, where he had lived and purchased a home with his British ex-girlfriend, Marietta Prokopé, in the 1960s. Though they had broken up, he and Marietta had remained close. She agreed to buy the rest of the house, leaving Abed with about 8,000 pounds ($19,200) after he paid off the mortgage. He and Viquar would use this to supplement what remained of the money they had raised in London. They would try to make life a little better for people like Sarabala.

* * *

Bangladesh was born a smoldering ruin. Most of the world had washed its hands of the country and its population of seventy million. In an oft-repeated phrase, an official with the Nixon administration remarked that the country, if it became independent, would be a hopeless basket case. “But not our basket case,” replied Henry Kissinger.

Abed landed at the Dhaka airport on January 17, 1972. Viquar soon arrived from the north, telling Abed in person what he had described in his letter from Sylhet, of the harrowing journeys people had endured. He had already established a makeshift operations center in an abandoned store in the market town of Derai, located in the center of Sulla. The surrounding area had been decimated. In village after village, the army had looted, burned the homes to ashes, killed the people’s livestock, and destroyed their farm tools. Abed and Viquar decided to focus their relief efforts there.

Abed went north to pick up where Viquar had left off. In Sylhet, he spent the night in the Gulshan Hotel, a cheap guesthouse. Accustomed to luxury, he was repulsed by the state of the room and the dirty sheets. The journey to Derai by road and river took up most of the next day. A local doctor, Manoranjan Sarkar, happened to witness Abed’s arrival at the dilapidated store Viquar had rented. “Around dusk, a gentleman wearing an overcoat with suit, tie, and boots showed up, accompanied by an elderly local man,” Dr. Sarkar recalled. “Not a sight you see every day.”

A group of locals gathered that evening, as Abed explained that he would need people to conduct a survey, distribute goods, and offer medical care. Most had lived in the camps. They needed work and were eager to help. That night, Abed climbed a rickety ladder to sleep in the dusty storage loft above the shop.

In Sulla, most people struggled to subsist even in the best of times. Abed thought his efforts would at least help people get back on their feet. The next day, he hired about fifteen literate people from the area to conduct a survey of destroyed or severely damaged villages. He instructed them to go from household to household, recording answers to a precise set of questions: How many people remain in the family? How much land do they own, if any? How many rooms were in the houses they had had before the war? How many cows? How many boats? How much had been destroyed? Abed gave them hours of detailed instructions on how to collect and record data, along with how to verify it by checking with the neighbors, so that people did not claim to have had more than they did. Abed found a local man with a master’s degree and put him in charge. “Send me the completed survey sheets every two weeks by courier,” he told him.

On the way back to Dhaka, Abed stayed again at the Gulshan Hotel in Sylhet. The conditions were exactly the same, but this time he reveled in the relative luxury.

* * *

Back in Dhaka, Abed hired a group of students from Dhaka University to help him analyze the data arriving from Sulla. Ever the accountant, he showed them how to organize the information into tables indicating exactly how much the villagers had lost: how many cows, goats, houses, and so on. The organization still didn’t have an official name, but it presented a good face to the world. Abed was executive director. It looked good to have a trained accountant who had left his job at a multinational oil company and put his own savings into the effort. For the board of directors, he and Viquar recruited a group of eminent Bangladeshis with impeccable reputations. The poet and social activist Begum Sufia Kamal, an icon of the nationalist movement, served as board chair. They called themselves the Bangladesh Rehabilitation Assistance Committee.

Viquar soon returned to London, leaving Abed alone at the helm. He still had the money from the sale of his half of the London house, plus $6,000 they had raised for Help Bangladesh. A representative of Oxfam, the British aid organization, told him they might be able to help. Using the Sulla survey data, Abed drafted a proposal for Oxfam to rebuild 6,500 houses, set up health clinics, build boats for fishermen, and more. In an internal Oxfam report dated March 16, 1972, Ken Bennett, the Oxfam overseas air director, wrote, “It is difficult to take an optimistic view of Bangladesh’s future.” Nonetheless, he noted his “favorable impression” of Abed and BRAC, which was “in the course of being registered” as a nonprofit organization. He recommended the approval of a grant of about $430,000.

On March 21, BRAC received its official registration. It was supposed to be a temporary relief effort, but Abed soon began to question the wisdom of this. Perhaps BRAC could replace a few thousand houses and farm tools, but would people’s lives be any different than before the war? He could go back to working for a multinational, but in Sulla, life would go on as it had for centuries, the landless tilling others’ soil with little to show for their efforts. What could the promise of liberation really mean to them? Theirs was not just a poverty of means but a poverty of freedom, opportunity, and self-worth. Relief work almost seemed futile in the face of it.

In the years to come, BRAC would grow—and grow, and grow. It is impossible to overstate Abed’s lifelong dedication to the cause, but if he were alive today, he would remind us of the hard work of millions of women like Sarabala. Along with other local women, she soon led the first BRAC group established in Anandapur, thus becoming, with Abed, one of the first leaders of BRAC.