Reimagining education technology solutions to address poverty in the Global South amid COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic has challenged the world to the core, underscoring the inescapable connections between public health, poverty, and education.

By Dr. Muhammad Musa and Radhika Shah

This piece was originally published in WINGS. It has been reposted below.

The Covid-19 pandemic has challenged the world to the core, underscoring the inescapable connections between public health, poverty, and education. The challenge for education technology, and the philanthropy that supports its innovations worldwide, is to improve this situation no matter what the local conditions. That requires adapting creatively, and we have already learned vital lessons on how to do that in Africa and Asia.

The World Bank estimates that the pandemic will push as many as 150 million people into extreme poverty in 2021. Simultaneously education, which is crucial to emerging from poverty, has been compromised through school closures and shifts to remote learning. Temporary school closures in more than 180 countries have, at the pandemic’s peak, kept nearly 1.6 billion students out of school; for about half of those students, school closures exceed seven months, the World Bank reports.

Access to remote learning is, in turn, greatly influenced by socioeconomic conditions. At least a third of the world’s schoolchildren — 463 million globally—could not access remote learning when COVID-19 shuttered schools, according to UNICEF. Disadvantaged children have been hit hardest by emergency measures, according to the United Nations.

The need for technologically innovative solutions for remote learning could not be clearer. Solutions must address five distinct but related elements: first, access to the internet, which is lacking in much of the world; second, in the absence of internet access, use of various forms of traditional media to augment remote learning; third, the necessity of adapting solutions to local circumstances; fourth, the varying needs of children of different ages; fifth, diverse family circumstances and dynamics.

The challenge is greatest in countries with low connectivity, but low-tech innovations born of necessity in those countries can benefit the underserved worldwide. Such innovations highlight the opportunity to leverage the power of philanthropy and technology to improve education and alleviate poverty.

The intersection of education and poverty

The intersection of enhancing education and alleviating poverty is underscored in the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which prioritise “No Poverty” as SDG 1 and “Quality Education” as SDG 4.

As Nobel Laureate and MIT Professor Abhijit Banerjee, one of the leading minds in development economics, states, “Poverty is not just a lack of money; it is not having the capability to realise one’s full potential as a human being.” Poverty is, therefore, inextricably linked to education, whose purpose is to expand our potential as human beings. SDG 4 is thus foundational for the next generation and all other SDGs.

Technology’s role in addressing poverty is vital, too. In a 2019 fireside chat at Stanford Business School, we discussed “Scaling Impact at the Intersectionality of Technology and Global Development to Achieve SDG #1” with Stanford Business School Professor Ken Singleton. The discussion examines the intersectionality of poverty, education, and technology.

Cutting-edge technological innovation, including artificial intelligence, is often cited as the panacea to achieving SDG 4 through remote learning in a post-Covid-19 world. But global progress toward ensuring inclusive, equitable, quality education was too slow before the pandemic, and inequities in education have only worsened since.

Prominent among them is inequitable access to online learning. The World Bank reports, “Only about 35 per cent of the population in developing countries has access to the internet (versus about 80 per cent in advanced economies).” This equity gap limits more than internet access: According to an analysis published by the Center for Global Development, in low- and lower-middle-income countries, only 50 per cent of households have access to radio or television.

Amid Covid-19, communities in the Global South created resourceful education innovations to address this stark digital divide. These innovations are needed to address the pandemic and other crises—including refugee crises, severe food insecurity, extreme weather, and conflict—which can be numerous, simultaneous, and layered. The innovations can be adapted worldwide, with applications for disadvantaged learners everywhere.

Stories from the Global South: Bangladesh, Tanzania, and Uganda

BRAC, the international development organisation headquartered in Bangladesh that reaches nearly 100 million people across 11 countries, has a long history of tackling poverty. It has vast experience providing education amid crises, ranging from the Ebola epidemic and the Rohingya refugee crisis to conflict in Afghanistan and South Sudan.

BRAC offers several models for delivering remote learning in low-connectivity contexts. In Bangladesh, Tanzania, and Uganda, BRAC adapts education delivery to each local context through television and radio broadcasts, telephones and mobile phones, and door-to-door outreach.

Television

On March 18, 2020, Bangladesh closed all schools and began televising lessons with BRAC’s support, and, for secondary students, assigning homework to be submitted when in-person classes resume. With many of Bangladesh’s students lacking access to television, BRAC created a home school programme conducted over basic phones. The programme reaches BRAC’s secondary students and offers subject-based learning, psychosocial support, well-being activities, and Covid-19 awareness.

Radio

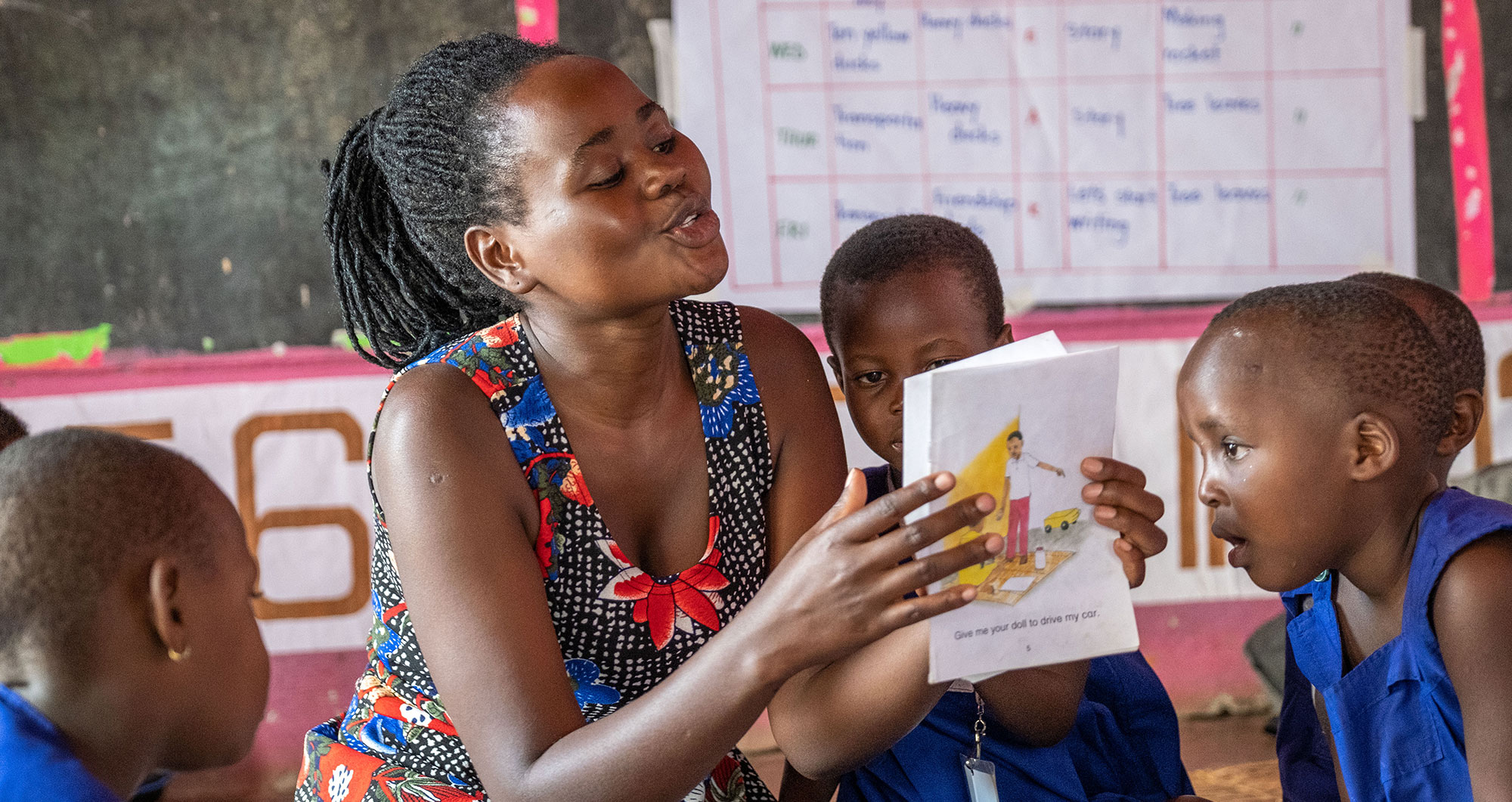

With in-person learning at BRAC’s flagship Play Labs not available for early childhood education during the pandemic, radio was identified as the most accessible platform for young children in marginalised communities in Tanzania and Uganda. Play Labs are vibrant, fun spaces where children aged three to five learn through an evidence-based curriculum that is centred around playful learning.

With support from the LEGO Foundation, which has been a key philanthropic partner in developing and supporting the Play Lab model since 2016, BRAC has adapted elements of its play curriculum and parenting curriculum for several avenues for remote learning, including radio. BRAC is using radio to share interactive playful activities for literacy and numeracy, hold storytelling sessions, and convey messages on child development, positive parenting, nutrition, safety, and well-being. In Uganda, where Play Labs are mostly in rural areas with limited connectivity, BRAC has partnered with two community radio stations to hold two Radio Play Labs sessions per week. In Tanzania, BRAC partners with the Tanzania Broadcasting Corporation for countrywide coverage.

Tele-learning

In partnership with telecommunications companies, BRAC launched tele-counselling and tele-learning hotlines using cellphones to connect parents and children with teachers, Play Lab leaders, and counsellors to provide continued psychosocial support and guidance on play-based learning at home. In Bangladesh, a model called Pashe Achhi, or “Beside You,” provides a national platform that started with psychosocial support in response to the pandemic and grew to include more support for caregivers and children specifically, including refugee families in Cox’s Bazar. In Tanzania, BRAC has collaborated with an existing national child helpline, run by the government and C-Sema. In Uganda, BRAC partnered with a major mobile network to establish a toll-free helpline promoted on the radio.

Text messaging and phone outreach

BRAC uses weekly text messaging and phone calls to share Covid-19 awareness messages with parents and continue children’s learning at home. BRAC has thereby reached more than 10,000 children and families in Uganda and Tanzania.

Door-to-door visits

Where possible, teachers visit families door-to-door to deliver hygiene messages and engage children through drawing and stories. In rural communities in Uganda, door-to-door visits have been particularly important. In Tanzania, where most Play Lab learners are in peri-urban communities, staff supplements door-to-door support by distributing learning packages that include crayons, storybooks, workbooks, and pencils.

The path forward: Philanthropy and technology joining forces

While technology and artificial intelligence can help create a richer, more engaging, remote learning experience, which all children deserve, we must first ensure access to the internet and to the most effective media resources at hand.

Solutions must be customized with partners who understand the local context. There is a need for funders—both philanthropies and impact investors—to finance such innovations, while embracing a co-creator mindset, in collaboration with organisations with deep experience on the ground and with technologists. There is also an opportunity to reimagine education technology financing by embracing collaborative and blended financing models where philanthropy can play a catalytic role and help de-risk later capital providers.

We can reduce poverty through education on a large scale if technology and philanthropy join forces with local innovators, academics, and policymakers to build research-proven solutions that are replicable. It is time to apply lessons from the Global South on how to shift our notion of innovation and scale to creatively design and fund solutions for the most disadvantaged children, even in the face of very limited digital infrastructure.

The SDG Philanthropy Platform catalyses collaboration within and across countries and sectors to achieve the SDGs. WINGSForum 2020-2021 brings together the global philanthropic community to raise their voices, share diverse knowledge, and reimagine a post-COVID world.

Dr. Muhammad Musa is Executive Director of BRAC International. Radhika Shah is Co-President, Stanford Angels & Entrepreneurs, Advisor to the SDG Philanthropy Platform, Illumen Capital (Fund of Impact Funds Tackling Bias), and Stanford Center for Human Rights & International Justice, and a Board Member of the Center for Effective Global Action at UC Berkeley.