Sir Fazle Hasan Abed’s life and work were marked by visionary thinking, practical action, and an unwavering faith in human potential.

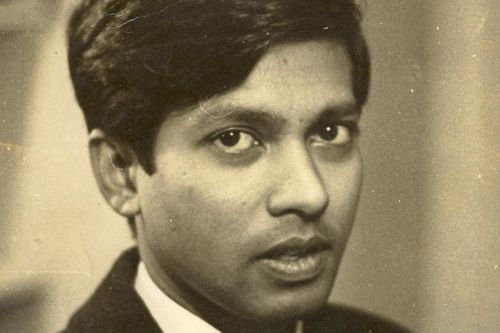

Sir Fazle Hasan Abed, or Abed bhai (brother) as many called him, was born in 1936 in Bangladesh. He studied in London, and went on to work as a senior corporate executive at Pakistan Shell.

Then, in 1970, a devastating cyclone claimed half a million lives in Bangladesh. He travelled with friends and colleagues to one of the worst-hit regions to distribute relief, and it marked a shift in his life.

The death and devastation that I saw happening in my country made my life as an executive in an oil company seem inconsequential and meaningless.”

Sir Fazle Hasan Abed

BRAC founder

A year later, the 1971 Liberation War in Bangladesh dramatically accelerated that shift. Abed bhai left his job and moved to London, where he helped initiate two civil society organizations to support Bangladesh’s liberation.

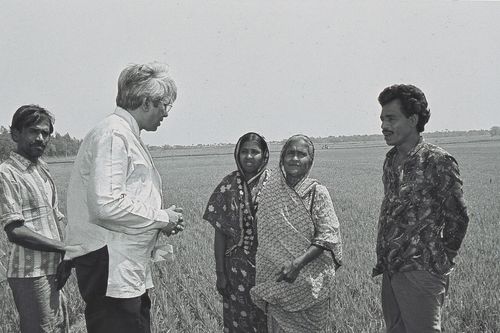

Early in 1972, when the war was over, he returned to the newly-independent Bangladesh, finding it in ruins. The return of 10 million refugees who had sought shelter in India during the war spurred urgent relief and rehabilitation efforts.

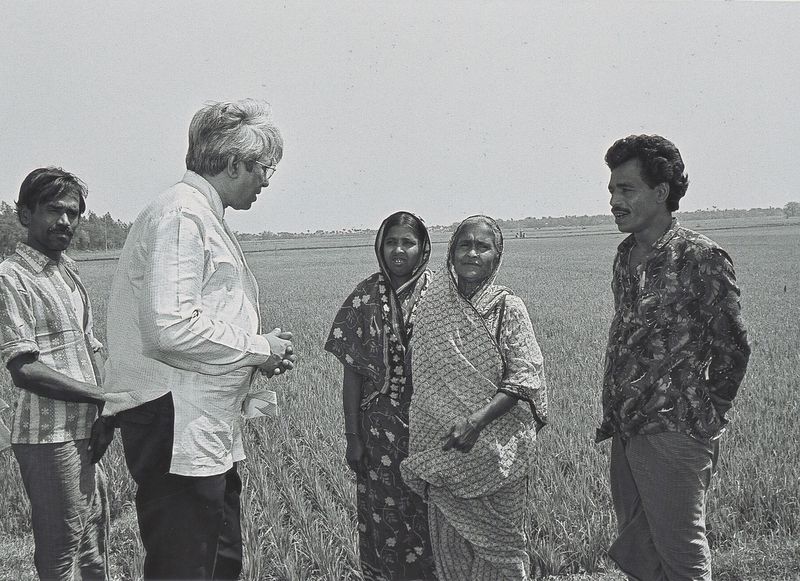

Abed bhai established BRAC to address the needs of refugees in a remote area of northeastern Bangladesh, guided by a desire to help them develop their own capacity to better manage their lives.

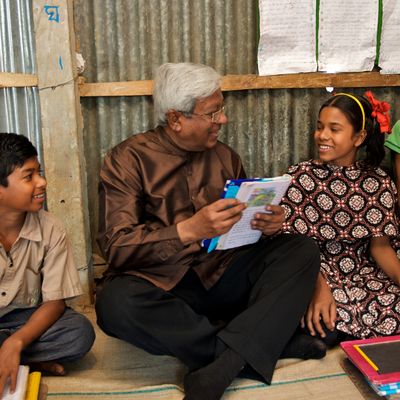

Abed bhai went on to dedicate his life to eradicating poverty and inequality. A legacy defined by bold vision and profound impact, he embodied, in the words of Nobel laureate Amartya Sen, the rare ability to combine “clear-headed thinking with sure-footed execution.” Driven by an absolute conviction in the power of people living in poverty to change their own lives, he saw development as unlocking potential through the right resources, opportunities, and, most importantly, hope. Central to his philosophy and life’s work was his unwavering belief that poverty and deprivation could only end by putting women in charge of their own lives and destinies. “I have met many defeated men,” he often said, “but I have never met a defeated woman.”

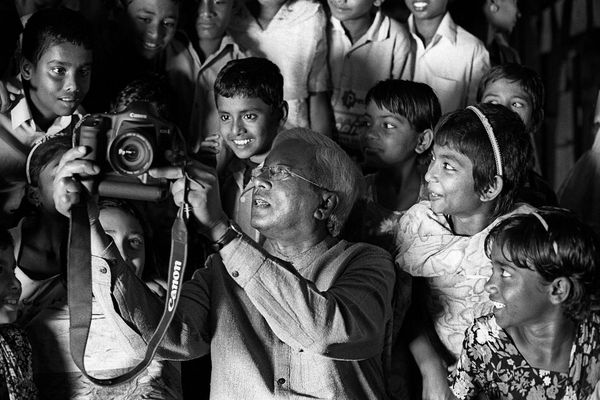

A true intellectual, with an equal love of Shakespeare’s sonnets and Tagore’s poems, he often recited poetry. He could recall poems of over 100 lines by heart, and often entranced staff with powerful, impromptu recitations. He was fascinated by books, art and culture, and quietly financially supported many social and cultural initiatives in Bangladesh, including literary festivals, the early films of Tareque Masud and other budding artists. He often expressed the aim of development as not just providing people with the opportunity to access basic human rights, but as providing everyone with the opportunity to enjoy art and literature. He undertook many literature-related projects, such as abridging almost 40 classic Bangla literary works for people with limited literacy, and then creating a system of community libraries, including mobile libraries on rickshaws and boats, to get books to every door.

Abed bhai used the analytical rigor of a chartered accountant and the compassion of a humanitarian to approach the world’s toughest challenges with boldness, pragmatism and an unwavering belief in people and communities. He believed visionary ideas must be matched with grounded, practical solutions—shaped by the complex realities on the ground. An unconventional thinker, Sir Fazle recognized the power of blending business acumen with development practice, always seeking simple, cost-effective solutions designed to scale beyond hundreds or thousands, reaching millions. His work connected solutions across sectors, building stronger systems and transforming lives at scale. With his leadership, BRAC grew from a relief effort into a pioneering force in global development. “Small is beautiful, scale is necessary,” he often reminded BRAC, urging the organization to think big and bold.

The inspiring legacy of Sir Fazle Hasan Abed

Remembering Abed bhai

Latest news

Standing where BRAC stands: my first journey as a BRAC USA Director

I saved my unborn daughter’s life, and also mine, by running away from a marriage

A hill village in remote Bangladesh dreamt of piped water. Then they built it themselves.